Interesting Articles Discussion Page

posted in Interesting Articles - 08/09/2009, 14:41

Lt. James Grant R.N. 1772-1833

(c) Irene schaffer

James Grant was baptized in the Kirk at Forres Morayshire, Scotland, on 6 September 1772, he was the son of Robert and Margaret Grant of Boganduie. Educated at King's College Aberdeen under Dr William Chalmers, from whom he learnt the elements of microscopy, as applied to botany and anatomy.

On leaving King’s College at the age of 21 James joined the Royal Navy in 1793 as a Captain’s Servant on the ship, Iresistible, from 26 August to 30 November, and from 7 December 1793 to September 18 1794.

Transferred to the Powerful from 2 May to 19 May 1794 as a Able seaman, From 20th May to 20 August as a midshipman.

His next appointment was on the Flora as Able seaman from 21 August to 12 September, and a Master’s mate from 13 September 1794 to 27 July 1797.

He then transferred to the Success on the 28 July 1797 where he served as Master’s Mate until 30 April 1799.

James Grant was discharged from the Queen Charlotte and took charge of the brig H.M.S. Lady Nelson on 19 October 1799, at £6 per month

His appointment to command the Lady Nelson as a Lieutenant came about because of his friendship with Captain John Schanck, who was then Commissioner of the Transport Board in London,[3] and the influence of Sir Joseph Banks.

In a letter to Banks in January 1800 Grant thanked him for his attention. Grant also mentioned the preparations of the Lady Nelson while she was in the River Thames.

`With nine months Provisions at Kings Allowance and six months water at a gallon each man a day – Boats, guns, anchor, eight in number & a proportional quantity of cables. Etc. etc. I can with safety run into seven feet of water only drawing six abaft. And with the use of the sliding keels I am enabled to haul off a lee shore equal to any cutter in the Navy. As I can increase the draft of water (forward or amidships) from six feet to twelve; in any one of the above places separately or altogether in the space of half a minute in time.

The Lady Nelson was launched on 13 November 1798 from Deadmen's Dock on the River Thames. She was designed with sliding keels, a device invented by Captain John Schanck, then of the Royal Navy. On completion she was selected for exploration and survey services in the Colony of New South Wales.

Lady Nelson River Thames 1800

The Lady Nelson was a brig of 60 tons and on instructions from Governor King in December 1800 the ship was to have a Lieutenant/Commander, a first mate, a second mate, a boatswain’s mate, a carpenter’s mate, a gunner’s mate, a clerk, an able and ordinary, and 8 boys of second class 2, on board. Unfortunately no documentation has survived to indicate whether these instructions were carried out to the letter. The Lady Nelson encountered trouble with keeping her crew intact while still in the River Thames, as it was common belief that such a small ship could not make it to the new Colony. Also other Navy ships needed crew for the war that was still raging. The boys certainly seemed to have stayed on board as Lt. Grant mentions the `lads’ throughout his journal.

Before departing from the Thames on the Lady Nelson, Lt. Grant married Ann Waters on 30 October 1799 at St. John Zachary with St. Ann and St. Agnes Lutheran Church in London. Ann was the daughter of Rev. Doctor Thomas Waters and Ann Stanton. Thomas Waters was the master of the Emanuel Hospital at Westminster in 1804.

Lieutenant James Grant set sail on the Lady Nelson from Portsmouth on the 19 March 1800 with a crew of thirteen. Arriving at Cape Town he was met by his cousin Dr. James Robert Grant, who was in residence there.

During his stay at the Cape his cousin introduced him to Dr. Brandt, a German who claimed he was a surgeon on a ship that was shipwrecked off the coast of South Africa, seven years previously. On his trek across the country to Cape Town Brandt befriended a dog and a baboon. These two companions he regarded as his best friends. He explained that they had saved his life, the dog by keeping away the wolves and hyenas, and the monkey by eating the food first, allowing him to know what was safe for him to also eat.

When Lt. Grant invited him to accompany the Lady Nelson to New South Wales, the doctor agreed, but only if he could take his two friends with him. After a three months stay at the Cape the Lady Nelson continued on her journey to Sydney leaving on 7 October 1800, accompanied by four unusual passengers, the eccentric Dr. Brandt, Jacko the monkey, the dog, and a huge Danish convict. The Danish convict! well, that’s another story.

The little vessel was the first ship to sail through Bass Strait from west to east on her way to Sydney, where she arrived on the 16 December 1800, nine months after leaving England on orders receiver at the Cape, that the strait had been discovered by Bass and Flinders shortly before.

All arrived at their destination without incident, except that the doctor was seasick all the way. The doctor and his friends setting up house on Garden Island near Sydney that had been given to Lt. Grant during his stay, and where the doctor grew vegetables for the crew on the Lady Nelson.

An Epitaph in the Sydney Gazette in 1804 of the death of a monkey, belonging to a gentleman in Sydney. The epitaph was accompanied by what is thought to be the first published poem in Australia.

It seems very unusual that someone would go to the trouble to do a memorial for a monkey . There is no clue that the gentleman was Dr Brandt or that the monkey was Jacko, but knowing how eccentric the doctor was, it was not an impossibility. (see Appendix for this entry in the newspaper)

Lt. Grant received very little praise for his accomplishing the long and dangerous voyage in a sixty foot brig, all the way form England. As far as King was concerned the ship had arrived at Port Jackson and he expected to get on with the surveying of the east coast as quickly as possible.

Grant remained on the Lady Nelson sailing south again on Governor Kings’ orders, in the hope of entering Port Phillip, but he only managed to get as far as Western Port Bay, where he surveyed Churchill Island on 31st March 1801, before returning to Sydney, he remained on the ship until his tour was completed.

Governor King was disappointed that Grant had not surveyed Port Phillip during the Lady Nelson’s voyage through Bass Strait. King expected Grant to take on the roll of surveyor, which Grant had not expected to do himself. He knew that the Lady Nelson was to do survey work and he was to be in charge of her, but he also expected that someone would be with him on board to do the survey work.

During the voyage out from England Lt. Grant had recorded many interesting discoveries both on the sea and on the lands he visited. His Journal unlike most log books kept by sea captains, goes into great details about fish, birds and animals and places. He was first and foremost a seaman with an interest in Natural History and Botany. He did not at anytime study mapping or surveying.

It is worth reading his journal and that of the Log of the Lady Nelson, written by Ida Lee[15]. In their different ways they portray an insight into the period of that time. During the voyage south in an attempt to again survey Port Phillip, Grant writes about his stay at Jarvis Bay, where he spent time with the aborigines. He explains in dept the friendly encounters he had with them on shore and on board the Lady Nelson. Also seeing their exchange with the two natives Worogan and his wife Euranabie who he had brought with him from Sydney

It soon became apparent to Grant that he was not fulfilling the roll that King was expecting of him and he volunteered to return to England were his services maybe of more use as a Naval Officer.

His voyage back to England took him through very rough conditions and he was not as happy as he had been on the Lady Nelson. The ship for the return journey was the Anna Josepha, which left Sydney on the 9 November 1801 for England via Cape Horn.Arriving in the Falkland Islands in January 1802, and departing later that month with favourable winds.

The Anna Josepha found herself becalmed off Tristan Da Cunha for over a month. Grant described this as being `A dreadful interval of time' He later recalled that at one stage he was reduced to one biscuit. A passing ship the Ocean transferred supplies to the becalmed ship and took Grant off the Anna Josepha and conveyed him to Cape Town, arriving there on 1 April 1802. After regaining his strength he embarked on the Imperieuse on 12 April and sailed for England.

Grant kept a journal of his voyage on the Lady Nelson, which was published in 1803 in England and later translated into French, German and Dutch.

On arrival back in London Grant was promoted commander in 1805 and while in charge of the Hawk was severely wounded in the field of action off the Dutch Coast He later resumed his service, first in the Raven in 1805, and then the Thracian.

Through the years a number of people have searched for descendants of James and Ann Grant without success, although family folklore records that there were descendants, with some suggestion that a branch of the family came to Australia in later years.

While concluding this book I happened to come across an entry in the Oxford Alumni Cantabrigians.

James Grant Adm. Pension, age 19 at Pembroke May 24 1838, eldest son of James Grant Esq. of St. Sarvan France. Born Worthing, Sussex. Studied maths. BA 1843.

Attempts to find his birth, or that of a younger brother, has been unsuccessful. It could be that James and Ann Grant may have had children, Ann would have been 41 by James’s birth in 1819, rather old for the first child. The absence of any mention of them in James Grant’s will could have come about because of their age, although there is no record of children on his death certificate. Future research may sort out if this James Grant was the son of Lt. James Grant or a relation.

James Grant’s whereabouts after his tour on the Thracian is not known, he seems to have retired to France, as his will was dated St. Servan 1825. James Grant Esq. died 5pm on 11 November 1833 at his residence at rue Duperre Saint Servan, France, aged 61 years. He was survived by his wife Ann (Waters) aged 56 years.

Last Will of James Grant, Saint Servan, France.

Text of the Last Will and Testament of James Grant.

Proved at London 8 April 1834 before the Worshipful John Dodson Doctor

of Law and Surrogate by the oath of John Grimault the son the Sole

Executor to whom administration was granted having being first

sworn to administer,

July 19th La Simonals St. Servans France.

In the Name of God Amen.

I, James Grant knowing that life is very uncertain and being at present in perfect health and sound mind Voluntarily make will and bequeath to my dearest wife Mrs. Ann Grant daughter of the Rev. Doctor Waters of Emanuel College Westminster. (commonly designated Lady Dacre’s Charity) the whole of my property personal and Real in any manner or way in which the above words can be construed. In short I mean that every thing of which I am possessed, personal or real or hereafter to be realized in case of my decease shall become, actually put into the possession of my wife as above designated and be of sole disposal without interruption or hindrance. I therefore pray all in authority or otherwise to aid and assist to see towards my dear wife carried into effect if called on her to do so and giving her as little trouble as possible for which care and attention the defunct hopes they will meat to rejoin in the resurrection which the just look for when time shall be no more. Written by me at the Le Simonais St. Servans France this nineteen day of June 1825. Signed and sealed. Jas. Grant Captain in his Britannick Majesty’s Royal Navy…………………………

Death Certificate

Commander James Grant at Saint Servan France. 1833.

Year eighteen thirty-three, twelfth November at ten o’clock in the

morning before us. Mayor of St. Servan, principal town in the

Department of Ille-et-Villaine, appeared Messrs Isaac Buxton,

fifty Five years of age, Captain in the English Army, and Alfred

twenty-five years of age, of no occupation, neighbours of the

deceased named below and declared to us that Mr. James Grant, sixty-on

years of age, commander in the English Navy, native of Aberdeen in Scotland, husband of Dame (Lady) Anne Waters, fifty- six years of age, native

of England. Son of the late Robert Grant and the late Margaret Sinclair his wife, passed away at his residence, house 6 ru Duperre, yesterday, eleventh

November, at five o’clock in the evening Signed I. Buxton A. Buxton.

Commander James Grant’s Grave. St. Servan, ru Duperre France

The top of the headstone is missing. Written on the base of the stone:

F L - - Grant

CONCESSION

Per Pet Uellel ?

James Grant progressed quickly through the Naval ranks, moving from a Captain’s servant to Commander in six years. At the age of 28 he was given the task of taking an extremely small ship half way around the world, sailing over the most dangerous oceans, and even though he had special passes to call at foreign ports, this did not automatically keep him safe from foreign ships at sea.[26] Strange as it may seem the only ships that challenged the Lady Nelson were British ships, ignoring the fact that she flew the Union Jack flag, with one ship chasing the vessel and another one firing its cannons at her.

Researching James Grant has been difficult. Even although his profile in the A.D.B. was very thorough, it left many questions unanswered. The A.B.D did not give references to his biography so it was a matter of going back and starting research from his beginning in Scotland. This was made difficult by the fact that, early Scottish Parish records are not readily available.

Nothing has been written about his earlier life in Scotland. An article in the Forres Gazette on the 8 November 1988, recorded that “Little is known of this remarkable man.”

Even though the Lady Nelson belonged to the British Navy she, like Commander James Grant, was soon forgotten. An inquiry in 1837 into the large amount of ships being sunk in the early 1830’s used to the Lady Nelson as an example as to how the earlier ships were built to withstand the rough weather. The inquiry referred to the Lady Nelson as if she was still sailing the Australian waters even though she had been captured by natives in the Timor Sea and destroyed in 1824.

More research needs to be carried out in England and Scotland. What has already been discovered about Lieutenant James Grant has shown a man who exhibited great skill as an officer in the British Royal Navy and left his name and that of the Lady Nelson forever in the pages of Australia history.

Further reading

The Usurper. Dan Sprod

Log Books of the Lady Nelson. Ida Lee; Website HTTP://www.electricscotland.com/history/australia/lgnel10.txt

First Lady The Story of HMS Lady Nelson. Lorraine Paul

John Bowen’s Hobart. Philip Tardif

Tasmanian Sail Training Association Ltd - website www.ladynelson.org.au Contains two log books of the Lady Nelson 1800, 1803 and 1804

Epitaph

On a monkey that usually occupied the summit of a high post in the yard of a

Gentleman in Sydney.

Beneath this pebble’d spot in death repos’d,

Lies the grim corpse of one estrang’d to care;

Was chattering oft, no secret onced disclos’d,

Who liv’d a captive… yet distain’d a tear.

A mind possessing a peculiar mould,

Alike to him was flattery and scorn;

And tho’ unclad, protected from the cold,

For bounteous Nature’s robe has never been shorn.

Devoid of talent, yet by fate preferr’d,

He lived exalted, died without disgrace….

Uncensor’d too!….nor has report been heard

T’ announce the next successor to his place.

Should the gay Coxcomb hither chance to stay,

Let sympathy provoke one kindred shrug;

And let his chatter through the wily way,

In doleful emphasis …. Alas poor Pug.[29]

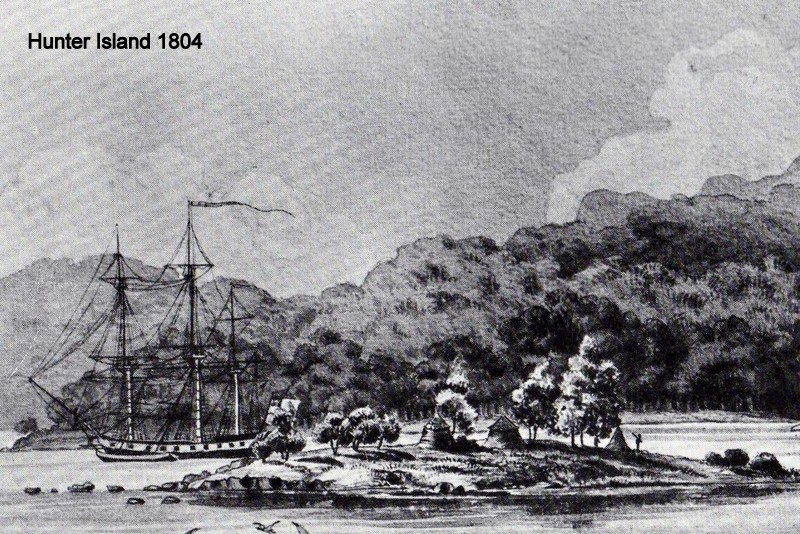

Lady Nelson in behind the Ocean 1804 Hobart Town

A complete coverage of this story in book form and photos can be obtained from Irene Schaffer irene.schaffer@bigpond.com

posted in Interesting Articles - 08/09/2009, 14:18

Bushfire at Fern Tree 1967, and our escape.

It was a Tuesday and the first day at Taroona High School for my eldest daughter Chris. Glenda my youngest daughter was also ready to catch the bus to the Macquarie Street School in South Hobart. Craig my son was only three and was at home with me.

Most of the men and older boys in Fern Tree for the previous couple of weeks had been helping to contain fires in and around the area, so when the siren went off at 7 o’clock that morning some of the men reported to the fire station, for the boys, it was off to school.

My husband Merve groaned and said as he had lost a couple of days without pay already, he had better go to work.

The morning continued in all its beauty, and even though the men had gone off to Nieka and beyond, the women continued on as usual. My neighbour Margaret came down to my place as arranged and gave me a home perm, thankfully getting to the setting stage. Another neighbour Jacky came and asked if she could leave her 9 months old son Roy with me, so she could go to Hobart, as it seemed as if it would be a hot day.

So with my hair in curlers, dressed in shorts and no shoes, Craig playing, and Roy asleep, I went on with my house-work. By lunchtime the day had changed completely, the wind had come up and smoke began to blow over the top of the house. Soon it was quite scary, here I was with two young children, no car, and no idea what to do. I expected every moment that Merve would walk in the door and do all the things that he would know how to do.

From the lounge room door I could see a few flames over towards Chimney Top Hill, across the valley. They shot up to the top at such a speed I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Once it reached the top sparks dropped down the other side and where ever they fell the bush would flare up, until the fires descended to the bottom, which was close to our place. The smoke became so bad that I couldn’t see above the roof. I kept listened to the radio and it was only then did I realize how wide spread the fire was.

Then the potaroos began hopping around the corner of the house, they had come from the gully behind and I dared not go and see what was happening there and leave the kids.

Time passed and I heard a voice, not Merve’s, but Cliff from over the road telling me to get the kids and come down to the road. I dashed around the house wondering what I should take! I tried to think of what valuables I had but nothing would come to mind, so I grabbed Roy from his sleep and the bag Jacky had left with his things in, and took Craig hand, shut the door and ran.

Thank goodness the men who were fighting the fire at Neika decided it was time to get back to Summerleas Road, or I don’t know what would have happened to those who were left there, mostly women and young children with only a few cars.

When I reached the road I found that the men had assembled everyone and was putting them in whatever car was available. I started off in a big car, but when the driver viewed Miss Campbell coming up her drive with two suitcases a hat over her arm and a friend in tow, he moved us into Shelia’s little red mini. We ended up having 3 women, 5 children and 2 kittens in the mini.

As soon as everyone was settled into the cars (about nine I think) we drove off up the road expecting to be able to get to the Huon Road and then on to Hobart. Not so, we only proceeded half way up the hill and were told by a council worker to turn around and go back the way we had come.

At this stage my mind is a bit blurry, I only know we went up and down Summerleas Road quite a few times, being turned back at the top of the hill and also about a mile the other way, because the flames were too severe.

At last the man in the first car took it on himself to make a decision and he went straight through the flames, which thankfully had subsided somewhat. We found ourselves in a burnout area, but still smoldering bushes and telephone poles all along the roadside.

I don’t remember what Shelia, Jean and myself said during this time, which seemed like hours, but it must have been less that an couple of hours. I do remember the five children, who were aged between 9 months and four years, never made a murmur. I had Craig next to me in the back seat and Roy on my lap, and one of the other children, and they never cried or wanted attention, they just sat there. It had become very hot in the car and though Jean had thought to bring some water and a wet blanket we had not been able to lower the windows as the sparks kept flying in on us. The poor little kittens were almost at their last, laying along the back seat panting for breath. The poor little Mini was a bit over crowded.

On reaching a somewhat safe spot about 2 miles down Summerleas Road, the cars stopped and the children were allowed out and placed in the middle of the road (most of them were so relieved at being able to have a pee).

That was the first time we were able to see who our companions and helpers were. It was a mixed bag, as not all of them were from Fern Tree. One I remember was from Marlyn Road and didn’t know how his family was fairing. We learnt later that it was very burnt out and some people died there. I never knew who he was, or if his family were all right. Others were from around the Huon Road with their older children, who had not returned to Collage at that time.

What I remember most is that there was no panic or complaining. We even had some laughts. One instance I remember was the hat Miss Campbell had over her arm was filled up with a packed of plums for the children one of the men had in his car. The elastic went down with the weight, but we all got a laugh from the look on Miss Campbell’s face. Her best hat full of plumbs.

We were scared and didn’t know what was ahead of us or if the fire was finished but it was decided we could only continue on. Further down we came to the first bridge, where we again stopped and the young people took the children down and let them paddle in the creek. Craig had only a pair of underpants on and ended up with a cold a week later.

The next bridge was still burning and we were not sure if it was safe to cross. On inspecting it the men decided it was, and that we could go on. From there it was not far to the township of Kingston. When we turned into the town it was like watching a war movie, there were people everywhere, sitting in the gutters with their heads in their hands, faces streaked with smoke, just sitting there, not saying anything. Some had suitcases, others, bags beside them. This was a shock as at that time we did not know that Snug had been burnt out and that some of these people had only escaped with what they had.

Again I don’t remember our trip up to Dynnynne where Sheila’s mother lived and where she was taking us. My thoughts were, where was Merve, why didn’t he come home, and where were the girls? The one thing that was good thing was that I had Roy to give back to his mother.

My son Craig is now in his forties but he can remember that day even though he was only three years old, nothing about the fire just that he has always remembered that I was worried because his father had not come home.

After ringing around for what again seemed like hours, Jacky came for Roy, but there was nothing about Merve. What had happened was that he was refused permission to go any further up Huon Road than below the Turnip Fields, even though he told the police he was trying to get home to his family and that he was also a fire volunteer for Fern Tree. I think he tried a couple of times but the bitchiman was catching fire and he had to leave. On his way down to Hobart he say a lady just standing on the side of the road. He stopped and told her to get in the car, but she said she had to get something from the house. He waited and finely followed her and found her standing in the middle of the room with her arms full of her husband’s suits. He finally got her and the suits into the car. Only a few hundred yards further on he found a couple on the side of the road near Hillborough Road. They at least had packed their belongings into suitcases, but the flames were coming up behind them, so they were lucky Merve came along when he did.

While I was waiting at Sheila’s mothers place, one of the visitors informed me that our newly erected house that we had built ourselves had been burnt down, I should have been devastated but all I could think about was where everyone was. One thing that I did think of was that my friend’s wheelchair was in the hallway. It had been sent from Brisbane as a spare while she was staying in Tasmania.

While I was waiting to have news about my family I watched the TV, well for a while I did. I could not bear to see what had happened and still was. Even though I had been in it myself, it looked a lot worse that what had happened to us while we were trying to escape.

Finally Merve arrived. He had been ringing the Town Hall (as many people were) and was told where I was. He had been frantic as when the trucks had arrived in Hobart with the people who had been caught at the Fern Tree Hotel, we were not with them.

While we were trying to get through to the Huon Road many residents on arriving at the Fern Tree Hotel were told they could not go any further. They locked their cars and some even had to leave their pets and went and assembled outside the hotel, hoping they would be rescued by someone. There were nearly 100 women and children of all ages all sitting and waiting. They watched the hall, store, fire station, pub and the Villa, all go up in flames around them. The church was found to be untouched standing amongst the trees at the Fern Tree Bower.

Speaking to many of them afterwards they said they thought it was all over, especially when someone came around telling the women to take off all their nylon underwear, as it would be the first to burn. Suddenly two trucks, that had been up on the mountain came out of the smoke. Everyone was quickly handed up on to the back of the trucks and wet bags thrown over them. These were the trucks that Merve was told had arrived in Hobart.

{Jean and Bern Pidd was amongst those who were caught in front of the hotel, at Fern Tree they were unfortunate enough to have moved to Kinglake some seven years ago and had their home destroyed there in Victoria’s worst bushfire in February 2009.}

When he knew we were all right, he went off to find the girls. Chris had been evacuated from the school at Taroona with other children, who usually caught buses to outlaying suburbs, and placed in the river. This was ok until burning tiles began dropping next to them in the water, having been blown of the burning housed further up the hill behind the school. She was later taken to a private home for safety, but that too became threatened and she was moved for the second time.

Glen was marched with the Macquarie Street School children up to the Barracks as the fire rushed down from Forrest Road towards the school. She was later taken to some of the houses on the Domain near Government House. She was later picked up by her father and bought back to the Dynnyrne where I was with Craig. Even though she is now 50 years old she has a bad time when she hears about a bush fire. On her way back with her father she witnesses a car accident near St. David’s Park. There were two very burnt passengers in the car and were thrown out on to the road. Not a very good sight for a 10 year old.

We decided to leave Chris with the people who had taken her in when she was evacuated for the second time and go back to see how our home was at Fern Tree. I had been told that our home had been burn down, but Merve told me he had been back and it was alright.

My mother was living at Chigwell at the time but of cause I never dreamed that the fire was out that far. She was alright but it did come up close to her fence, and there were homes and the local school burnt down. Many other suburbs were in danger as the fires had spread far and wide.

It was a bit of a horror trip going up Huon Road as some of the trees along the sides of the road were still burning and many of the power poles where on fire and falling down near the road. We arrived at the junction of the Huon and Summerleas Road but it was too dark to see what had been burnt down. Later the next day we learnt that the pub was gone as well as Street’s store and the hall and the fire station. The Villa was also destroyed, this was a fine old home behind the hotel where we had stayed when we first arrived in Tasmania in 1960 before moving down to Leslie Farm.

Travelling down Summerleas Road we were stopped by one of our neighbours Mr Gray who wanted to know who we were as there had been some looting, when he saw it was us he signalled us on.

At last we arrived home, everything was quite as most of families had not yet returned. Cliff Davis who lived across the road called out “who the bloody hell are you” we were more scarred of being accosted by the neighbours than the fire. But they were only looking out for their neighbours who had not returned to Summerleas Road. Cliff said it was so hot in his house and could the boys come up and sleep on our concrete floor.

As small fires were still flaring up every now and then we decided to take turns at sleeping and keeping an eye around the house, it was well we did as a small fire broke out under out trailer about 7am. Looking around the next morning there was not a blade of grass anywhere to be seen. A house next to Leslie Farm survived but when the owner went to get his family and bring them home he found it had caught alight after he left and it was gone.

On arriving home and going in the front door we were overcome with the smell of burnt wood and beer. The back part near the house had caught fire when the wind swept some leaves under the eves setting the beams alight. Roy the little baby I was looking after lived a few doors from us and his father Alex Skelenica had walked from Hobart to his house and was very lucky to save as it was circled by fire. After making sure it was safe he walked along the road to see if there was anyone in need of help. He was almost blind from the smoke and his ears and head was burnt. When he arrives at our house he noticed there was smoke coming from the roof and thought it was our combustion stove but decided to have a look. As soon as he opened the door he realized the roof was on fire.

Finding there was no water in the taps, he looked around to see what he could find and came across our homemade beer in a rubbish tin in the corner of the kitchen. Dragging it up the bank to the back of the house he was able to step across to the roof and by pulling off some iron he was able to pour the beer over the fire and put it out. That was why the house smelt like a brewery.

A large number of Summerleas Road residents lost their homes, out of 57 homes only 17 remained. The fire raced up and down and across the mile long road taking a house here, leaving four on the other side only to race back and take another four further up the road. Leslie Farm was one of the first to go being an old timber house it didn’t stand a chance. We had spent 7 years there and it was sad to hear it had gone. The Smith family who owned it had only escaped with the clothes they had on their backs.

The death toll was very high over the worst burnt out areas, 62 in all, so we were relieved to hear that none of out neighbours were missing. Mr King, down past where we lived died later from burns he had received.

Our home was the only one standing in our immediately area four had been taken and only ours remained standing even though a bit scorched.

We were without electricity for over 3 weeks and our combustion stove came in handy and we were able to offer our neighbours food and hot drinks for the next few days.

My neighbour who had permed my hair lost her home before leaving and going down to the cars she places her caged bird on my kitchen table and when she returned that was all she had.

I remember the author Patsy Adam Smith coming to our door (she was a friend of Miss Campbell boarder) and asked if I would roast some legs of lamb for friends of hers down the channel who had lost everything.

When there was nothing more I could do at home I went down to the wharf and helped distribute food and clothing to families who had lost their homes. This was organized by the Girl Guides Association and again there was no sigh of panic or demands, people just lined up and were grateful for what they received.

Over the next few months we gradually started to live normal lives, some families did not return but many did. Homes were rebuilt and looking back now at what I have seen and heard of other disastrous fires throughout Australia I realize that we did not get the counselling (not heard of in 1967) everyone just got on with it and helped themselves and their neighbours.

Because it was so sudden and was all over in a day there was not the usual radio or TV coverage especially in the Huon Road area and mostly only those who lived from Longley to South Hobart were aware of how close we nearly lost over 100 people at Fern Tree that day.

Even though the fires only lasted one day there were 60 lives lost with 900 people injured and 35,000 people effected and 7,000 people left homeless. And the loss of 1,293 homes lost along with 1,700 buildings, 80 bridges, 62,000 livestock, an overall cost of $101,000,000,00.

Because I was a guider in the Girl Guides Association I was sent to Mt Macedon in Victoria for a week to discuss what should be done in the case of the bush fires returning in later years. Can’t remember much except their advised was to stay in the car. I did not agree with this advise then or now. There will never be a right or wrong way as no two fires are the same.

This was not Tasmania’s first bushfire nor will it be our last, our bush will always prove a problem and what the answer is has been and will be discussed long into the future.

(c) Irene Schaffer 2008

posted in Interesting Articles - 09/01/2009, 10:32

Magazine articles of interest to Tasmania.

The Tolman Quilt from NewTown Tasmania

A "champ" of a library table by William Hamilton

The creation and furnishing of Government House Hobart

David Collins' blackwood tea caddy: and open letter to the trade.

Australiana Magazine November 2008 Vol. 30 No. 4

posted in Interesting Articles - 30/12/2008, 09:55

The End of a Long Journey

The story of the beginning of a new life for those convicts and soldiers who arrived in NSW from 1788. Their years on Norfolk Island and their final chapter in Van Diemen's Land.

Talk presented at the Bowen Lectures at Rokeby in 2007 by Irene Schaffer.

Booklet - The Fourth Annual Bowen Lecture, 9 September 2007. punblished by Eastern Shore Historical Network inc.

Available from Eastern Shore Historical Network inc. and viewed at the Tasmanian Reference Library.

posted in Interesting Articles - 30/12/2008, 09:39

Lady Nelson H.M. Pioneer of Australian coastline.

This story is about the original Lady Nelson built in 1798 in the River Thames. Her adventures, her work on surveying the coast of NSW and voyages to Norfolk Island and Van Diemen's Land from 1800 - 1813, until she was lost in the Timor Sea in 1824.

Article in Australian Heritage autumn 2008

Written by Irene Schaffer.

posted in Interesting Articles - 30/12/2008, 09:25

From Norfolk Island to Van Diemen's Land

Story of the arrivals of the Norfolk Islanders who came to Hobart Town in 1807-8. Wih some beautiful photos.

This article is also in the Australian Heritage Autumn 2008

andavilavle in libraries and newsagents.

Written by Reg Watson

posted in Interesting Articles - 30/12/2008, 09:18

Norfolk Island Island of changing fortunes.

This interesting article and photos covers the early settlement of Norfolk Island as well as the present time on this beautiful island.

Written by Brian Hubber for the Australian Heritage Autumn 2008. Available in libraries and newsagents.

Irene